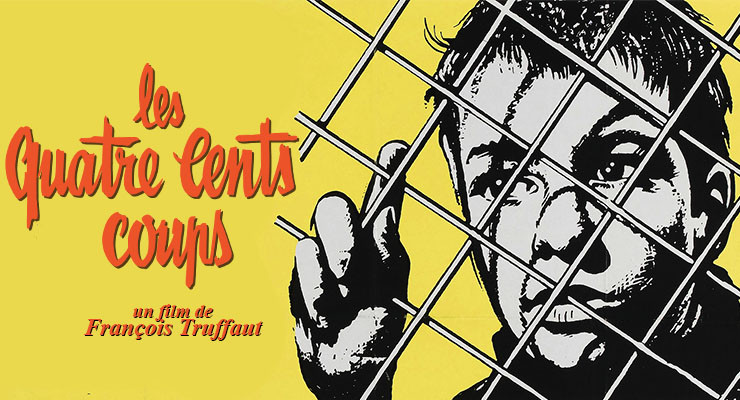

400 HUNDRED BLOWS, THE (QUATRE CENTS COUPS, LES)

(director/writer: François Truffaut; screenwriter: Marcel Moussy; cinematographer: Henri Decaë; editor: Marie-Josephe Yoyotte; music: Jean Constantin; cast: Jean-Pierre Léaud (Antoine Doinel), Patrick Auffay (Rene Bigey), Robert Beauvais (School Director), Claire Maurier (Mme. Doinel), Albert Remy (M. Doinel), Guy Decomble (The French Teacher); Runtime: 101; MPAA Rating: NR; producer: François Truffaut; Janus; 1959-France-in French with English subtitles)

“A movingly sympathetic and perceptive portrayal about an unwanted rebellious adolescent.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

This is 27-year-old film critic François Truffaut’s, an admirer of film critic André Bazin, auspicious debut film. Though not his best film, that honor would have to go to Jules and Jim, but one that first gained him an international following as a member of the French New Wave. It still stands up today as a marvelous work that in its simplicity and intensity was a movingly sympathetic and perceptive portrayal about an unwanted rebellious adolescent. The 13-year-old Antoine Doinel is superbly played by the 14-year-old Jean-Pierre Léaud. The lad is bored with school and made to feel unwelcome at home by his working-class parents, who have a less than perfect marriage and hide their unhappiness by pretending everything is fine. Antoine’s mother is having an affair with the boss, which he knows about when he spots them kissing in a street cafe on the day he was truant, and his clownish aloof father is spending his leisure time with his weekend racing club. Antoine, the filmmaker’s alter ego (much of the story is quasi-autobiographical), is aware that his father married his attractive mother when he was a small child and let the illegitimate child take his name. He’s constantly reminded by his mother of his father’s generosity, which does little to bring the two closer. As an 8-year-old, Antoine was shipped out to live with his grandmother who returned him to his parents when a few years later she got too old to take care of him.

Antoine finds school stifling, and as a result of teaming up with his likewise rebellious classmate Rene gets into trouble constantly in school with pranks and by having failing grades. He especially irks his uptight French teacher (Guy Decomble), who catches him passing around a girlie pinup centerfold during an exam and then catches him scrawling insults on the classroom wall when he’s left in the classroom alone while his classmates take their recess. His self-centered mother treats him coldly and can only communicate in a positive way by trying to bribe him with money for good grades and behavior, while his crude father doesn’t have the ability to reach the quiet but pensive youngster and thinks he did enough for him by letting him have the same last name.

When Antoine shows us he can be stimulated by the cinema and literature but gets an “F” for an inspired essay on Balzac, which the teacher believed he plagiarized, he runs away from home and foolishly steals a typewriter from his father’s office in the hopes of supporting himself while on-the-run. When he can’t sell it the watchman catches him returning the machine, and the father turns him over to the police. They place him in an Observation Center for Delinquent Youth, where he escapes. The film’s memorable last shot is a frozen image of Antoine’s anguished face as he is on the beach by the sea. That ambiguous ending leaves us wondering if he reached freedom or was this the beginning of his doomed life, as he reached this crossroad in life where he can’t turn back.

The odyssey of Antoine Doinel was continued in Stolen Kisses (1968), Bed and Board (1970), Love on the Run (1979), and one short, Antoine and Colette (1962), as we watched him grow up and find love.

REVIEWED ON 6/8/2005 GRADE: A-